Are we training too many optometrists in Australia?

Update: Please note that in mid-2014 Optometry Australia released the results from a report stating that there would be a significant oversupply of optometrists in Australia by 2036, that will be starting from 2016. Please expect a competitive jobs market on graduation if you are considering becoming and optometrist. Please also see our August 2015 article on what optometrists can do to stay competitive in the jobs market.

Following is the original article as it was published on 24th February 2014:

A marked increase in the number of optometry students graduating from Australian universities is expected to occur by the beginning of 2016, even though a study from 2009 concluded that the population to optometrist ratios at the time were more than adequate to meet the needs of the community. Just to add in some confusion, the profession “optometrist” had a labour market rating of “shortage” by the Australian government in 2013, and is on the Skilled Occupation List.

Want more information? Let’s have a detailed look at what’s happening with the labour market for optometry in Australia….put it under the magnifying glass (yes, optometry joke intended). And just a warning, there are lots of graphs and stats in this article, so please feel free to scroll down to the summary at the end!!

1. Number of optometry graduates from Australian universities

The numbers of optometry graduates from Australian Universities:

- 1989 to 1998 – approximately 100 each year (source Optometrist Labour Force 2009)

- 2001 – 200 (source Eye health labour force in Australia)

- 2002 – 152 (source Eye health labour force in Australia)

- 2003 – 205 (source Eye health labour force in Australia)

- 2004 – 212 (source Eye health labour force in Australia)

- 2005 – 174 (source Eye health labour force in Australia)

- 2006 – 265 (source Eye health labour force in Australia)

- By 2016 there will be approximately 360 (source Optometrists Association Australia) optometry graduates (an increase of 35.8% compared to 2006) – the increased supply of graduates from Australian universities will be due to the first graduates coming out of Flinders University in Adelaide (end of 2015, approx. 30 graduates) and Deakin University (mid 2015, approx. 70 graduates) in Geelong

Data from Health Workforce Australia showed that from 2008 to 2012, approximately 1 in 6 graduates of Australian optometry schools were international students. Assuming these numbers stay the same, you could expect approximately 300 domestic graduates per year will come out of Australian optometry schools from 2016.

2. Age of optometrists currently registered in Australia

The Optometry Board of Australia most recently released its registration data in October 2013. According to this report, there were 4,659 optometrists registered in Australia. Of these 4,532 optometrists were practising optometrists with general registration, and their age groups were as follows:

- 179 (3.9%) were aged 24 years or under

- 1322 (29.2%) Were aged 25 to 34

- 1182 (26.1%) were aged 35 to 44

- 1065 (23.5%) were aged 45 to 54

- 656 (14.5%) were aged 55 to 64

- 128 (2.8%) were aged 65 or over

It becomes quite clear that, if the majority of the graduates are aged 34 years or under (as is historically the case), there will be a very high proportion of young optometrists in the labour market in the coming 5 to 10 years as the number of university graduates is increased. Obviously these graduates would be expecting longer careers than those aged over 55, who make up a smaller proportion of the optometric workforce.

3. Employed full-time equivalent optometrists per 100,000 population in Australia

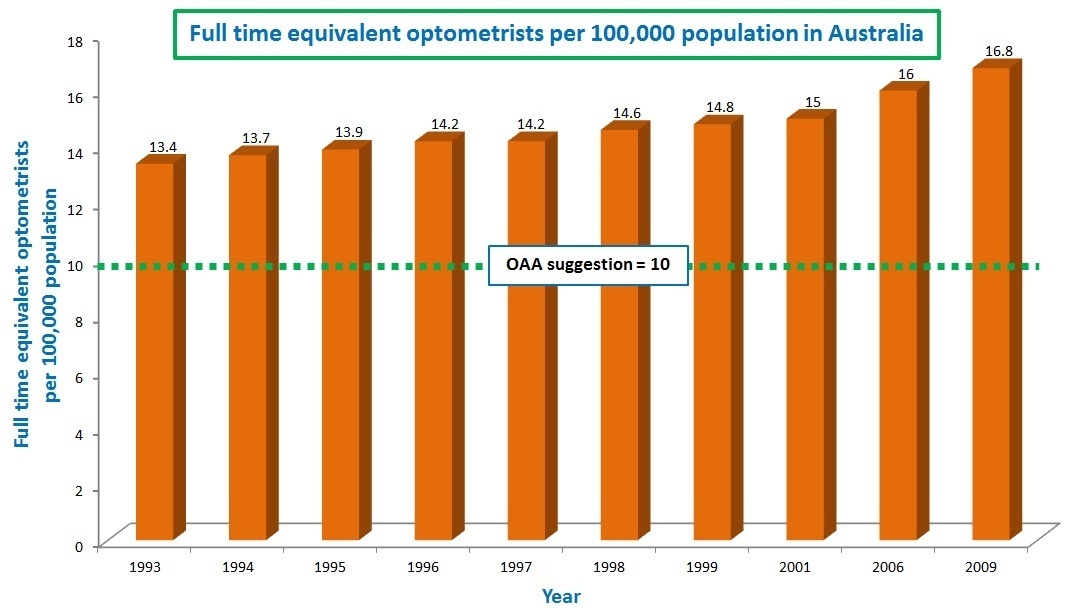

In its submission regarding the health workforce in 2005, the Optometrists Association Australia stated that the ratio of one optometrist to ten thousand people in the Australian population “is generally regarded as adequate.” This ratio suggests that about 10 optometrists are required to service a population to 100,000 people. Graph 1 shows that the numbers of optometrists in Australia exceeds this figure, and continued to increase in the last 20 years:

Graph 1 – Employed full-time equivalent optometrists per 100,000 population in Australia

(Sources: Optometrist labour force 1999 – Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Eye health labour force in Australia – Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, The Australian optometric workforce 2009 – Kiely, Horton and Chakman)

4. Migration of overseas optometrists to Australia

Specsavers has been pitching partnership opportunities in Australia to optometrists from the UK for a number of years. Specsavers articles have appeared in publications such as Optician Online, as well as in their own Careers Guide 2012 (see page 12) and blog Spectrum. Specsavers has also run ads in Optician Online. The first testimonial on the Australia & New Zealand Joint Venture Partnership page is of an optometrist who had owned a Specsavers store in the UK in the 1990s, and is now a partner on the Gold Coast. Health Workforce Australia data shows that relatively small numbers of optometrists have been granted temporary or permanent Visas in Australia. The peak over the last few years was 2010-2011, with 26 temporary 457 Visas and 44 permanent Visas being granted.

5. “Feminisation” of the optometric workforce in Australia

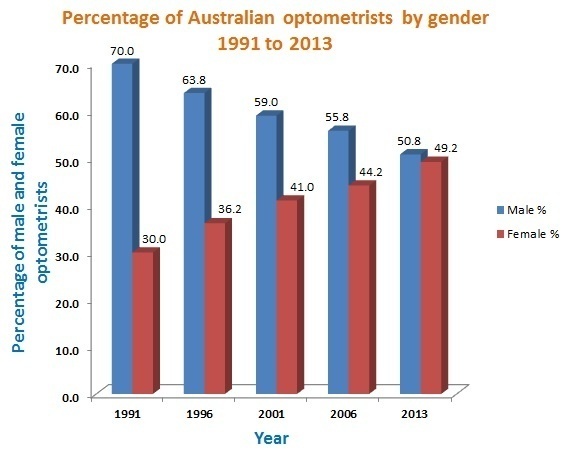

The following graph says it all really!! 20 years ago optometry was a male-dominated profession, but more recently there is almost a 50/50 split of male and female optometrists.

Graph 2 – Percentage of Australian optometrists by gender 1991 to 2013

(Sources: Eye health labour force in Australia – Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Registration Data Table – October 2013 – Optometry Board of Australia)

The Australian optometric workforce study 2009 showed that on average, male optometrists worked 40.3 hours per week, while females worked 32.9 hours per week. Obviously there has been a trend for females to work part-time hours. If more females go into the profession, this could mean that the overall number of practising optometrists required is increased because women tend to work part-time hours, and so more of them would be required to make up the equivalent full time optometrists needed.

6. The Ageing population

A report from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare showed that the ageing population will drive growth for optometry services. It would be useful if more exact research was done to predict how many more optometric consultations per year are required to account for this growth. Data from the AIHW showed that in 1998-99, the number of services per 100 people in the population was 9.5 for those aged less than 10, 32.4 for those aged 45 to 54, and 34.0 for those aged 65 to 74. It predicted that the proportion of the population aged 45 and over would increase from 34.5% in 1999 to 43.8% in 2019, therefore causing an increasing number in the number of optometry services per head of population during this time frame.

7. Demand for optometric services and consumer habits

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s report Optometrist Labour Force 1999 showed that the number of Medicare services rendered by optometrists in Australia increase by 30% from 1992-93 to 1998-99. There were 3.9 million consultations which attracted Medicare benefits in 1998-99.

Optometry as a profession in Australia came of age in the 1970s when it became part of the Whitlam government’s Medibank (now known as Medicare). It was the start of a transition from ophthalmologists delivering primary eye care such as screening for eye disease and checking spectacle prescriptions to having the optometrists doing these tasks. Anecdotally, I would estimate that approximately 30 to 50% of people I examine for sore eyes, red eyes or foreign body removal have been to a GP or pharmacist first. I simply have not been able to find any data on how many see a pharmacist and are treated successfully, or see a GP and are treated successfully or are referred on to an ophthalmologist and thereby bypassing the optometrist.

8. The most recent Australian workforce study

The Australian optometric workforce 2009 was published in 2010, and the findings were:

- The number of optometrists in Australia was more than adequate to meet the needs of the community

- New South Wales had a ratio of 1 equivalent full-time optometrist to 5,247 people in the population. That is, 19 optometrists per 100,000 population, almost double the OAA suggestion of 10 per 100,000. There were 11.5 optometrists per 100,000 population in South Australia

- In New South Wales, the average optometrist spent 20.1 hours per week doing Medicare and Veterans Affairs consultations, while it was 30.6 hours per week in South Australia.

- The data suggest that optometry practices on average, won’t be as busy where there are greater numbers of optometrists per 100,000 population

9. Optometric supply and demand predictions

The study Optometric supply and demand in Australia: 2001 – 2031 showed that if their projections were correct, there would be an excess of 6.9% of optometrists compared with demand by the year 2031. If there is a high growth of the number of optometrists, there would be an oversupply of up to 30%, and if there were low growth, there would be an undersupply of at least 21.5%.

However, this study was completed in 2007, well before Flinders University and Deakin University started to produce optometry graduates. In this study, it was assumed that there would be a constant 120 graduates per year. We now know that there are a projected 360 graduates per year from 2016.

SUMMARY

What is certain at this stage is that there are an increasing number of graduates, and also an increase in the demand for optometric services due to the ageing population. Graduates may need to go to areas where there are fewer optometrists per 100,000 people in the population to find a job. Assuming that a similar rule of thumb applies as it traditionally has in Australia, the job opportunities are generally in the states which do not have a school of optometry, with Western Australia and the Northern Territory often having fewer optometrist per 100,000 population.

If we adjust the figures from the Optometric supply and demand in Australia: 2001-2031 study to take into account the increased number of optometry students who will graduate, you can predict a surplus of optometrists in Australia by the year 2031 unless other variables in the equation change. A new workforce supply and demand study is presently being undertaken. There will always be opportunities for optometrists who have skills in building a business, and can build a referral base, for example, from general practitioners and other health care professionals in their local area.

More articles and resources on My Health Career:

One reply to “Are we training too many optometrists in Australia?”

Same happened in UK commercial driven institutes drove up the amount of optometrists which over all lead to over supply and hence a vast decline in salary